I recently saw a protoype Arri Amira for the first time. I really, really like most of what I saw, but some of it needs a rethink.

I recently saw a protoype Arri Amira for the first time. I really, really like most of what I saw, but some of it needs a rethink.

I know the gang at Chater Camera exceptionally well, and in spite of that they invited me to their Arri Amira open house on February 12th in Berkeley. Last year I participated in an Arri new product survey in which I asked for a camera like Amira and I was excited to see how close they got to the vision that I, and many others, presented to them in regard to a low cost “Alexa Jr.”

Arri's Snehal Patel answers a question for John Chater in one of Chater Camera's prep bays. The camera at left is an Alexa in studio mode; the camera on the right is an Amira in full-on doc mode.

Based on what I saw I think Arri got a lot of things right. I think they listen more than many camera manufacturers do but there are a couple of gotchas with the camera design and pricing strategy that have me scratching my head.

This camera is going to shoot HD only, and do it beautifully. I hear “4K 4K 4K” constantly but most of my work (spots, high-end corporate branding and marketing pieces) has a short lifespan and much of it is landing on the web. Unless I’m shooting a VFX project I don’t need $K resolution; instead I want beautiful color, highlights that roll off smoothly and gently, and dynamic range comparable to film. I get that from Alexa now, and nearly everything I’ve shot with that camera has been to ProRes4444 HD. Amira stands a good chance at replacing Alexa for most of that work while saving production money. Well… a little money. (More on that later.)

I shoot with nearly every camera under the sun and I can make pretty pictures with all of them, but Alexa makes my life a lot easier than the others. I really like the speed and dynamic range of the Sony F5/F55 cameras, although their colorimetry (particularly the crazy saturated yellows—although this appears to be fixed in SGamut3) occasionally gives me pause, and the menu structure is the most complicated of any camera I’ve worked with. Canon’s cameras make flesh tone look great but the combination of 8-bit processing, comparably low dynamic range and unpleasant highlight handling prevent me from putting their cameras first on my list. RED cameras are quirky: as one camera assistant I work with says, “Every serial number is also a model number.” Panasonic is effectively out of the game unless I want to shoot with an HDSLR, which I don’t always. In spite of that fact that there are a lot of choices out there at the moment, but the only one that makes me truly happy is Alexa.

As I wrote here, Arri does color amazingly well and it’s killed me that I don’t have the budget to get that look on every shoot. I’m hoping Amira solves this problem.

I’m not going to go into this camera in the kind of technical detail that Adam Wilt does. Instead I’m going to focus on usability issues and price. Here’s the quick hit list:

-

Amira uses the same sensor and color science as Alexa, so it’ll give me the same Arri color that I love so much.

-

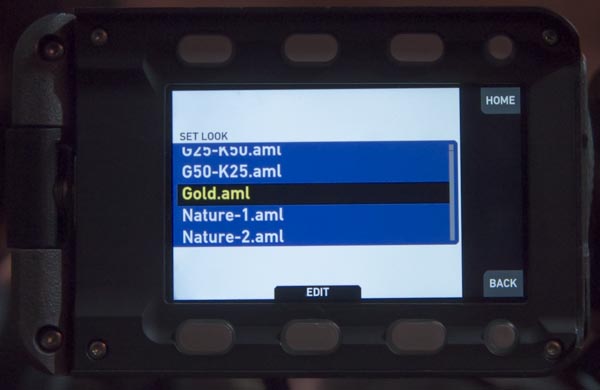

Not only will I get that look but I’ll have access to a number of alternative built-in presets that are adjustable in camera.

-

I’ll be able to create my own looks for use in the camera. The workflow looks like it’ll require shooting some footage in Amira, bringing that into Resolve, crafting a look, exporting that into an ASC CDL, bringing that back into Amira via USB drive, and loading it up as the active look. (This has not been finalized yet.)

-

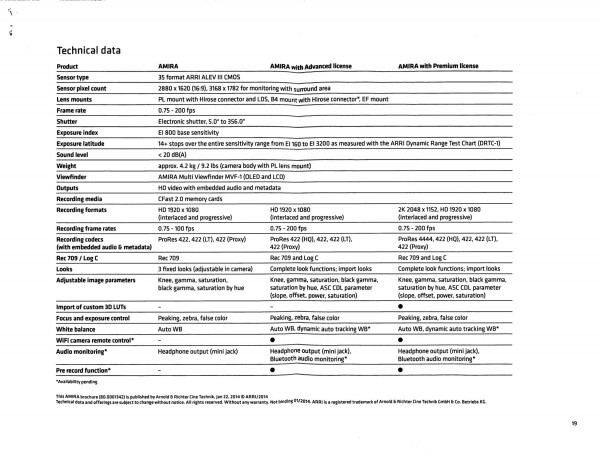

Framerates from .75 to 200fps, depending on the license purchased for the camera. (Licenses are available as both permanent and temporary upgrades.)

-

Field-changeable lens mounts (PL, B4 and EF).

-

ProRes422, 422HQ and 4444 depending on the license purchased.

-

Camera weighs ten pounds.

- It’s designed to record sound the way an EFP camera should, which will make the sound people happy.

The Arri Amira with a Fujinon 19-90 EFP lens attached. The lens weighs as much or more than the camera does. Note the LCD on the side of the viewfinder: more on that later.

The camera is light. Really light. I don’t know how much of that is due to advances in technology vs. the camera not having to output 4K raw files, and I don’t care much. It’s going to be a joy to handhold.

The operator side of the Amira.

Remember I said there were things I liked about Amira and things I didn’t? Several of each are visible on this side panel. First, the good:

I like the three round switches just behind the PL mount. The bottom one is for white balance and offers three presets plus auto tracking as a fourth option. The three presets can either be set manually via the menus or by aiming the camera at a white reference and pushing the “set” button (between the record switch and the WB knob). Auto tracking attempts to adjust white balance on the fly, and although I’ve not seen Arri’s version of it I know that both Sony and Panasonic have implemented this in many of their cameras and it tends to work very well for run-and-gun doc work.

The second knob from the bottom is labeled “EI” and stores three exposure index presets that are adjustable via the menus. Whereas on a camcorder I might have -3db, 0db and +6db as presets I can do the same thing here by programming, say, 400, 800 and 1600.

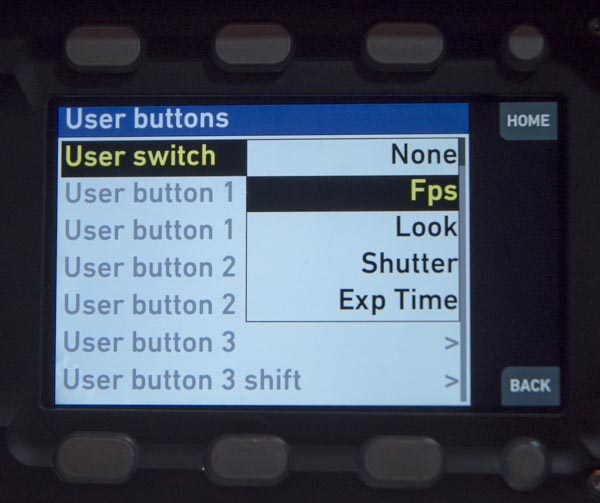

The top knob is labeled “5”, which threw me until Arri’s Jim Davis told me it was the fifth programmable function controller. The four buttons in the middle of the picture—labeled, conveniently, one through four—are programmable user presets. I don’t know exactly what it is that they can be programmed to do because that function wasn’t enabled on this particular prototype, but they’ll likely do some useful things. The button at the bottom of that column, labeled “2nd,” is a shift key that maps an additional four functions onto those four function keys. (Here’s hoping that button is renamed “shift” on the production models.) Whereas buttons 1-4 (and 5-8 with “shift” enabled) presumably toggle functions on and off or change the overall state of the camera, knob “5” (referred to as “user switch” in the menus) contains a variety of presets within a single function’s range. At this time the available options are speed (FPS), Look, Shutter and Exposure Time, and putting knob “5” into any of these states gives us an additional three adjustments within that state.

The options for user switch "5", subject to change.

My hope is that this knob is renamed “user switch” in the production models, to match the menu, as “5” is a bit of a non-sequitur. If I hold down shift and push button four, which button is that really? I would have thought that would be button five. (Jim Davis of Arri pointed out several times that this was a very early prototype, so I suspect all this has changed).

The side of the camera is visually attractive, but not very useful. I never thought I’d say this, but Arri should have taken a hint from decades of camcorder design when they placed these function buttons as well as the audio controls under the display and the display itself.

The Amira is designed for one-person operation. It’s just not designed for one-person continuous operation. If I’m operating the camera and I want to access function buttons 1-4, or the shift or lock keys, I have to tip the camera away from my head to get at them. There’s no easy way to quickly push a function key.

The lock button is in a worse position. There’s a possibility that an operator could balance the camera such that the function buttons are accessible (although not with the Fujinon 19-90 zoom that was on this camera as the lens was heavier than the camera) but placing the lock button toward the rear makes it much more difficult to reach.

Side display in audio mode.

A good EFP sound person sets the camera and mixer up at the beginning of the day and spends the rest of the time swinging a boom or monitoring radio mics. They don’t do a lot of level checking at the camera as they are monitoring the audio return and can hear if something’s gone wrong. Still, they do like to take a peak at audio levels from time to time, which is why the side display on camcorders is placed well to the rear of the camera. This makes it easy for an sound person to sneak a look at sound levels whenever they happen to be near the left side of the camera. Great EFP sound people will also take responsibility for making sure time code is set correctly and is running, etc. In a way they’ll act as a second set of technical eyes for the cameraperson, as they have a lot more time as sound is really pretty easy. (HA! Not true, but I had to say it.)

Hiding the camera display behind the operator’s head prevents the sound person from performing any of these additional quality control duties.

Some aspects of the design are genius. For example:

Controls on top of the viewfinder: Peaking, exposure check (presumably false color), two function buttons, a record button and an EVF button (not sure what that's for yet.)

The controls placed on top of the viewfinder are genius. It’s not unusual for an EFP cameraperson to grab onto the viewfinder to either steady the camera or adjust it in some way, so it makes perfect sense to make some of the more crucial camera functions available from there.

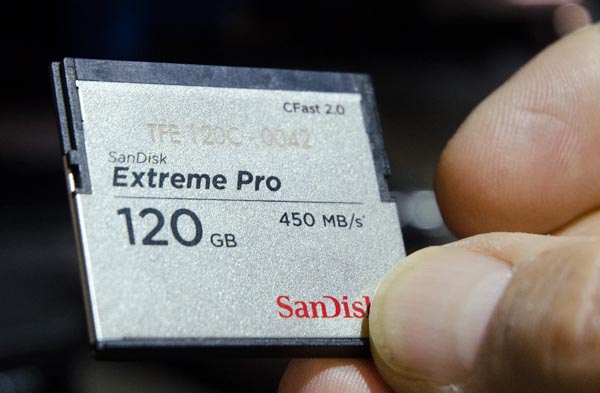

I also like the media storage area and the CFAST 2.0 card setup:

CFAST 2.0 media slot (top) with two USB ports and an Ethernet port.

Camera assistant Paul Marbury models the Amira's CFAST 2.0 card.

I don’t know much about the media itself (it’s the “new hot thing,” apparently) but I do know that it snaps into place nicely when loaded into the camera, compared to an SxS card which simply slides in until it can’t go any further.

If I were designing the controls layout for this camera, though, I’d make a number of changes:

(1) Put the function buttons where the front air vents are, or create a classic control tray toward the front of the camera.

Here’s a side view of a Panasonic Varicam 3700:

Panasonic Varicam 3700

Here’s where they put the most crucial camera functions:

Function tray on a classic camcorder.

Years and years ago, when I shot with a lot of cameras built in this style, I knew these controls very, very well. “Save, ” which parks the spinning tape heads so they don’t stay in contact with the tape when the camera isn’t rolling, isn’t used anymore, but gain and white balance are, and “output” controlled whether the camera generated color bars when pushed one direction and engaged highlight control circuitry when pushed in the other. I knew where all of these were by touch, although in my very early days I found I could look down while shooting and see where the switches are.

Note that the “monitor” (headphone volume) and “alarm” (how loud the camera beeps over the headphone output when something goes wrong) knobs are set far enough back that they fall roughly behind the operators right cheek, and yet they were somehow always accessible. (More than a couple of times I felt the sound person’s nimble fingers reaching past my face to adjust the headphone volume.) Compare their placement to the function buttons on the Amira prototype:

The eyepiece is probably pushed too far forward in this picture, but still… those side function buttons are going to be really hard to get at unless the operator tips the camera away from their face for second or two in the middle of a shot… which tends to ruin the shot.

I’d feel a lot better if all the controls left of the side display fit into the space where the three function knobs and the cooling vent are now. (Oh, and about that cooling vent… the camera is effectively hollow, with the electronics built around the outside of the camera body, so air flows silently through these vents through the center of the camera and out the rear. The interior is completely sealed against dust and moisture. Pretty cool.)

The eyepiece is attached to that top bracket, and that bracket slides back and forth a LONG way. It’s wonderfully adjustable. Still, I’m not sure how the operator’s head doesn’t block everything useful on the side of the camera.

If I were to go further I’d say swap the media storage module with the display module. That way the display is always visible to the sound person and the only time the operator needs to tilt the camera away from their face is when they have to change a card—at which point they’ve stopped rolling anyway.

The good news is that the classic Alexa control interface has been moved to the viewfinder’s flip-out LCD, which makes it exceptionally easy for the operator to look at menus with their left eye while looking through the viewfinder with their right eye.

(2) Rethink the lock and shift buttons.

The Amira’s lock button is exactly like Alexa’s lock button: hold it down for two seconds to lock or unlock all the side panel buttons. In ENG and EFP environments, however, two seconds can be an eternity.

If I were designing this camera I’d combine the lock and shift buttons, at least for first tier functions. Put the lock button where the shift button is now, so it’s actually reachable by the operator while shooting, and allow the function keys to operate if the lock button is pressed and held while the function key is pressed less than two seconds later. Perhaps a double press of the lock key shifts the function keys… although, honestly, I don’t know when I’d need eight quick function keys on the side of the camera. (It’s not entirely clear what they can be programmed to do yet anyway.)

(3) Rethink the location of the shoulder mount slider release.

That dark object hanging off the bottom of the camera, to the left of the Amira logo, is the shoulder mount slider release.

The shoulder mount is wonderfully adjustable: it’s extremely easy to find a way to a balance the camera comfortably even with a heavy lens. Unfortunately the release lever for the sliding shoulder mount is on the opposite side of the camera in the rear, making it impossible for one person to adjust the shoulder mount and lock it themselves. (I’m hoping this is only the case on the prototype.)

(4) Rethink the pricing structure.

I know I’ve been excited about Amira for quite a long time. I live in a secondary market and it can be difficult at times to get an Alexa on a production in place of any of the much cheaper cameras out there, in spite of the fact that having one saves me a lot of time as I can light and flag much more simply than I can with a cheaper camera. I’ve worked hard to recreate the Alexa look in other cameras and I can get close but there’s still nothing like an Arri to give me that filmic look that I crave. So… imagine my surprise when I learned the base model is going to run about $40,000.

To put this in perspective, this was the price of a new Sony F900 when it was released 15 years or so ago as the premier HD production camera. We’ve come a LONG way since then, and $40K is pretty cheap if you can put this into historical perspective. Still, it’s hard to make a convincing argument when “competing” cameras run $25K less and do a bit more—like shoot 4K.

Do I think 4K is a big deal yet? No. Do producers? Yes, many of them do, and as they buy cameras for their production companies—and many are!—they look for gear that gives them the longest run for their money. Many are convinced that 4K, rather than amazing color and dynamic range, is the key to longevity, and at a lower price point I can make a very good case for that. The higher the price the harder that is to do.

When it comes to price, technology always wins over artistry. I wish that wasn’t the case, but the money people tend to look at tangibles over intangibles and it’s hard to point to a camera and say, “That camera’s color is going to sell your product better than anything else in its price range!” It’s true, but color isn’t quantifiable. Resolution is.

Not only does Amira come with several Arri presets, but in theory you'll be able to design your own and either use them as viewing LUTs or baked-in looks.

There really isn’t any reason to shoot 4K unless you want to seriously future proof a feature or TV series or shoot visual effects plates, and most short form productions don’t have a long enough shelf life to warrant a 4K master. Amira is aimed squarely that that market segment, but they already have other cheaper HD-only options available. Arri quality is second to none in terms of build quality and color, but it’s sometimes difficult to sell that to someone who is trying to ensure that they get the most life out of their investment. Arri Alexas hold their value better than any camera in recent history: they’re still the most sought-after high-end production camera four years after their release, which is something of a record since the RED ONE was released in 2007 and changed the lifespan of the average camera model forever. Still, before that, it was possible to own a Betacam for ten years, pay it off in a year, and then make money off it for another nine, and those who buy cameras still dream of those days.

I can see Amira being attractive to owner/operators at $30K, but $40K has me worried.

What has me worried more is that the base model is essentially unusable. According to this spec sheet the best recording spec is ProRes 422, which I don’t consider suitable for mastering. ProRes 422HQ is the minimum quality that I’ll shoot and that’s not available without paying another $5K for the next tier.

A fully kitted-out Amira (without lens and support) is going to run close to $70K! That seems quite a lot for an HD-only camera. Will Amira be worth the price? Absolutely! Will it be a tough sell to anyone outside of large institutions and rental houses? Yes. This isn’t really an owner/operator camera for the run-of-the-mill EFP crowd. This is a premium product.

Amira's eyepiece has a LCD display built-in. Shooting in bright sunlight? Use the viewfinder. Shooting a low shot running after some children? Fold out the LCD and use it instead.

And, in the end, that’s what it’s all about: paying a premium for a premium product that delivers exceptionally well. While I quibble about usability issues the fact is that Amira is built like a tank, has fantastic dynamic range, a smooth filmic look and color to die for. Unless 4K takes off in the next couple of years (it may or may not—there’s no way to watch it yet, so that puts a bit of a damper on things) HD will be here and viable for a while. It’s reasonable to expect this camera to have a solid three or four year run before something else comes out to replace it. Are there cheaper options? Sure… but you still get what you pay for. I just hope enough people are willing to pay Arri’s price.

I use a lot of Apple products in my business because they just work. They’re well designed and they don’t break easily. I’m willing to pay a premium for that. When it comes to imaging Arri is in the same class, and I’m hoping my clients are willing to pay for that class. In the end it makes us all look better.

About the Author

Director of photography Art Adams knew he wanted to look through cameras for a living at the age of 12. After ten years in Hollywood working on feature films, TV series, commercials, music videos, visual effects and docs he returned to his native San Francisco Bay Area, where he currently shoots commercials and high-end corporate marketing and branding projects.

When Art isn’t shooting he consults on product design and marketing for a number of motion picture equipment manufacturers. His clients have included Sony, Arri, Canon, Tiffen, Schneider Optics, PRG, Cineo Lighting, Element Labs, Sound Devices and DSC Labs.

His writing has appeared in HD Video Pro, American Cinematographer, Australian Cinematographer, Camera Operator Magazine and ProVideo Coalition. He is a current member of the International Cinematographers Guild, and a past active member of the SOC and SMPTE. His website is at www.fearlesslooks.com.