“What is that?” my gaffer invariably jokes as I pull out my light meter on set. Meters are rare in the HD world, but I’m revisiting my film roots and using them more and more. These days I won’t be caught without them.

Film was always a bit of a mystery to me. There’s something magical about making a series of lighting, filter and exposure choices having to wait a day to see that they resulted in beautiful images. My goal as a film DP was predictability: I wanted to have a very good idea what I’d see in dailies. To some extent I trusted my eyes, but eyes (or brains) are easily fooled. I learned to trust my spot meter.

My years as a camera assistant were very informative. I stood by the camera and watched DPs take meter readings and then put their requested stop on the lens; the next day I saw the results while sitting next to them in a screening room. No two DPs had exactly the same metering style, though. Some worked entirely with an incident meter, others with a spot meter, and most with some combination of the two. Several DPs shot black-and-white Polaroids to determine exposure.

My desire for predictability drove me into the spot meter camera, as I wanted to place specific tones on specific values (a la The Zone System) and I got pretty good at it. I’d frequently confuse myself, though, by trying to read too many things at once and trying to assemble all those pieces in my head.

I didn’t trust incident meters at all. They only told me how much light was falling on an object but didn’t tell me anything about how bright the object itself was. I felt like I was working in the dark with an incident meter, and I held others in disdain when I saw others using incident meters to average exposures across multiple light sources. In my head I thought, “You’re averaging light sources! How can you possible know what’s going on with any single light?”

As I transitioned into the video world I learned to use zebras and waveform monitors for exposure. This appealed to my critical side as I could see exactly how bright or dark something was. A waveform monitor is the ultimate spot meter.

This, however, didn’t help much with lighting continuity. Waveforms are great for matching exposures, but they don’t help much when you have to match light levels from shot to shot while maintaining the same f/stop. Often I’d expose for consistent flesh tones, which was problematic as flesh tones in the real world aren’t consistent: some people are brighter or darker than others.

Using spot meters with HD cameras was problematic at best. I brought spot meters on scouts to determine whether I’d see detail outside a sunlit window with a given camera but I rarely used them on set. Every camera has its unique set of gamma curves, and without memorizing the characteristics of every curve it was difficult to use a spot meter with any kind of predictability.

I learned to simply light by monitor and waveform. This worked for me for quite a long time, but eventually I grew restless. I hated being tied to a monitor, especially when CRTs drifted away and LCD replacements weren’t really color accurate, and when raw cameras came onto the scene producers wouldn’t pay for a waveform monitor anymore. I still needed to create consistently-exposed images, as I wasn’t being invited to the color grading sessions anymore and I wanted to preserve my artistic intent as much as possible, but I wasn’t completely sure what to do.

My work for DSC Labs, maker of high-end color charts, taught me that most of the reflected light values in the world fell into a predictable range between 2% reflectance and 90% reflectance. I found that I could estimate these values by eye, based on my knowledge of the values found on color charts. (4.5% reflectance is a matte black, while 90% reflectance is a matte white.) I learned that the most critical tones in video were the two stops above and below middle gray, between 20% and 80% on a waveform monitor: nearly all the really important tones in an image fell into that range, while the rest were largely gravy.

I gave my incident meters another look.

Incident meters don’t care about gamma curves the way spot meters do. All an incident meter does is make middle gray look like middle gray, while allowing values around it to fall naturally into place. There’s some variation in that four-stop range based on the gamma curve employed by the camera, but I learned that an incident meter can be a great way to set a consistent exposure for those crucial mid-tones that make all the difference in any picture. (Our eyes naturally roll off, or compress, highlights and shadows. Mid-tones are where the meat is.)

I own five or six meters, and just prior to a recent travel job I laid three side by side to see how they matched. They didn’t! I’d had two calibrated a couple of years ago by the excellent Quality Light Metric in Hollywood, but they’d clearly drifted over time. I’d calibrated the third myself, to match the other two, and now none of them said the same thing. They all varied by about a half stop. (A half stop is a big deal in HD.)

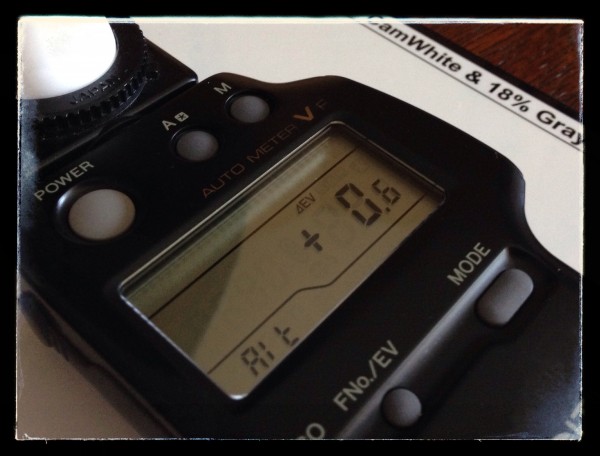

I didn’t have time to ship them all to LA for calibration so I packed the one that was easiest to adjust (a Minolta Autometer IV) along with a DSC Labs OneShot Plus chart. The back of the OneShot Plus is a combination 90% white and 18% gray card, and I devised a cunning plan to calibrate my meter to the specific camera I was using.

At the first lighting setup I placed the gray card in front of the camera and used the internal waveform monitor to place the 18% middle gray portion of the card at 40% on the luma waveform. I then placed my incident meter in front of the card and took a meter reading. I compared the stop on the meter’s readout with the stop on the lens (with shutter speed and ISO matched between the camera and the meter) and used the meter’s built-in offset capability to match it to the stop on the lens. After dialing in a 6/10 stop offset I used my meter to set exposure for the rest of the shoot, and it worked consistently and perfectly.

Although I primarily use incident meters with HD, spot meters can be “calibrated” in this same way. Light a gray card evenly, set the camera’s exposure so the gray reads 40% on a waveform monitor, and adjust the meter to match the camera’s stop (with shutter and ISO being the same on both camera and meter).

Middle, or 18% gray, falls at 41.7% on a luma waveform monitor in Rec 709. While middle gray can be placed at different values in various log curves, I always go by a camera’s Rec 709 output, even if I’m recording in log, as I don’t monitor log at all. If it looks good in Rec 709 I know I’m capturing more than enough data to make it look great later in a grade. I keep an eye on highlight clipping but otherwise I have no interest in seeing a flat image.

Where I used to be Mr. Anal Retentive and meter everything on the set with a spotmeter, I now light by eye, set the exposure for the most important thing in the shot (usually a face) with a light meter, and then judge the rest of the image by looking at the monitor. If I need to match key and fill levels then I’ll write them out on a piece of tape stuck to the back of my meter and tweak my lighting from shot to shot, keeping a consistent f/stop on the lens. Occasionally I’ll turn on the monitor’s built-in waveform and check out the highlights, but I’ve now done about a dozen jobs where I don’t turn it on at all.

The one thing that I need to do is test this calibration method under both tungsten light and daylight. Light meters primarily measure the green portion of the spectrum and filter out red and blue, so measurements of saturated red and blue light may result in readings that are excessively low. Because of this I don’t know if my calibration method is skewed by the fact that the camera may see more blue and red spectrum than my meter does. The amount of green in daylight and tungsten is roughly the same, with the biggest changes being the ratio of blue to red, so theoretically my meter should read the same under both kinds of light. However, the luma waveform uses a complex calculation whereby the brightness of a light source is derived from a formula of (approximately) 70% green, 20% red and 10% blue, so middle gray on a luma waveform may appear to be too bright as it may be factoring in spectrum that the meter can’t see. Better practice might be to calibrate the meter using a parade RGB waveform and placing green at 40% while ignoring red and blue.

Calibrating a meter to a camera is not technically correct, and may not even be good practice, but in a pinch it has worked very well in helping me maintain a consistent look over the course of a project. I’ll still send them down to LA to get them calibrated, but I’m also going to experiment with one meter and try matching it to whatever camera I’m using at the time. I’ll be curious to see what results.