One of my guilty pleasures is watching the HBO series “True Blood.” It’s a campy vampire soap opera, true, but it’s also occasionally educational. Episode three of series seven got me thinking a lot about craft, and how it’s being lost…

One of my guilty pleasures is watching the HBO series “True Blood.” It’s a campy vampire soap opera, true, but it’s also occasionally educational. Episode three of series seven got me thinking a lot about craft, and how it’s being lost…

TV is where it’s at these days. When I was growing up, TV was a formulaic wasteland where shows were cranked out quickly in front of flimsy sets lit poorly by hard lights. The turning point seemed to be the 1990s series “30 Something”: I didn’t watch it very often as I wasn’t 30 something at the time and the subject matter didn’t particularly interest me, but the look was very, very different to anything I’d seen on U.S. TV previously. It was lit very softly and realistically, much the way commercials were (and still are), which was most definitely not the way most TV shows of the era were photographed.

I had a chance to walk through the “30 Something” stages one day while working on the same studio lot (on a sitcom called “Evening Shade”). Whereas most TV show sets of the time were lit with a combination of space lights and fresnels, the “30 Something” sets were covered with bleached muslin and ringed with 1K fresnels spaced a few feet apart. To light a corner of the set quickly all one had to do was turn on a nearby fresnel and the space was illuminated by a beautiful soft glow. Low angles were no problem as the unlit muslin looked like a white ceiling.

Toward the end of my career as a camera assistant I worked with a very old school DP who’d shot a lot of television in the early 70s and 80s. Her work was not very subtle: she placed hard lights everywhere and I often lost count of the multiple shadows. Her show was the last on the air to transfer from an internegative; I could tell from the look (the show was lit high key but still showed very high contrast) but when I asked her whether the production company was having the negative scanned or if they were using an intermediary step she responded, “I don’t know.” She was hired because she got a lot done in a day and she did it very pleasantly, and although the show we were working on shot a 48 minute episode in only five days (modern shows typically shoot a 42 minute episode in eight days) we had a lot of fun doing it.

“30 Something,” on the other hand, was clearly transferred directly from the negative and lit with what was then a commercial aesthetic, and while it was shot quickly it was not a “factory” show. It had something to say, and the producers gave the crew the tools and the direction to say it well.

These days TV is where it’s at. Feature films are almost an afterthought, and indeed I find myself going to fewer movies than ever before. Instead I find myself staying home and watching amazing televison on HBO, Netflix, cable, and occasionally a broadcast network. The typical episodic DP has to turn out feature-quality work while shooting 8-10 pages a day in multiple locations. There are some shows that are shot (in my opinion) better than others, but the overall quality is crazy better than what I saw as a kid.

In the old days TV series directors were basically traffic cops: the actors knew their roles, and the director told them where to stand and figured out how to cover the action so a scene would cut together. It was a no-frills business. Over time series developed to the point where you could see the imprint of individual directors on episodes of some of the classier shows (for example, there was a noted difference between episodes of Twin Peaks directed by David Lynch versus anyone else, for example, and especially the one directed by Dianne Keaton) and suddenly big time feature film director names started popping up in TV series credits.

In extreme cases you see shows like Netflix’s House of Cards, where nearly every episode is directed by an A-list feature film director. Other shows, like True Blood, shake it up a little: I’ve seen shows directed by cast members, and one of their DPs did a guest stint directing the final episode of the last series. The one that made the biggest impression on my so far, however, was episode seven of season seven, directed by Simon Jayes.

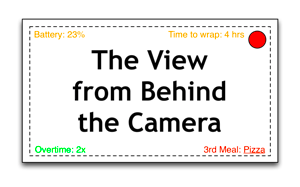

When I saw his name on the director title card I sat up a little straighter. He was the show’s long time A-camera operator. My original dream was to be a professional camera operator because I wanted to be the one framing all the shots, although I later discovered that this duty fell more to the DP and the director than to the operator. I’ve always been fascinated by composition and how scenes cut together, and I was excited how someone who looked through cameras for a living would block and cover a scene. I was not disappointed: his choice of shots was tasteful but markedly different to the norm, and he made some wonderful coverage choices. It was a visual treat. (Disclaimer: I tend to tune into the extreme subtleties of cinematography, so if you saw this episode and didn’t notice anything different, well… trust me on this.)

It got me to thinking about my own work. I tend to enjoy crafting scenes out of shots that flow together with a purpose. Even though nearly all my work is shooting spots or high-end corporate I’m always looking through the lens of someone who grew up watching narrative film and television. I dreamed of creating images that cut together with a purpose, not simply capturing them and figuring it out later… but so many of my clients, and my competition, seem so focused on doing the latter that I sometimes despair for my craft.

A couple of years ago I saw a documentary about DPs in which one of the questions was, “Do you consider yourself a director of photography or a cinematographer?” All but one of the interviewees said they were a cinematographer. The reason? They were the ones who were responsible for crafting the image. It’s easy to read that sentence quickly and not see anything special in it, but the key word is “crafting”: they MADE their images, with intent formed from reading a script, to tell a specific story.

Unfortunately I see lot of younger “cinematographers” who are really only camerapeople. A cameraperson, specifically the “first cameraman” in the silent film days, was in times past the director of photography, but I’m redefining that term to mean someone who can frame pretty shots but isn’t a director of photography or cinematographer. Camerapeople don’t craft images, they capture them–and probably create most of the look later in the grade. A cinematographer goes into a project with a solid idea of how it will look, executes that idea as best they can, and turns footage over to post in such a way that their intent is clear. Color and contrast and brightness can be changed in a grade, but the shape of the light generally can’t and neither can the choice of camera angles and lenses.

The floaty handheld look is all the rage these days, and there are some who do it really well. Facebook’s “Paper” promo is a great example of this: it has an easy, free-floating doc feel and yet every shot was boarded, and specifically lit. I know a couple of people who refuse to believe that this wasn’t shot entirely doc-style, but it clearly (at least to me) wasn’t.

Still, there are a lot of “cinematographers” out there who shoot almost exclusively in this style and don’t plan out their shots nearly as well, and it’s so widely accepted that I’ll get directors asking for this: “I don’t want a big crew or a lot of gear, I just want to grab a camera and see what happens!” This approach certainly works for some things, but not everything–and, more often than not, I discover that a director who asks for this doesn’t really have a strong vision for a how a spot should look. They just want pretty shots and they’ll figure out the story in the editing room.

I don’t know that I would call those who only shoot in this style “cinematographers,” or “directors of photography.” Shooting doc-style is a awesome skill, but it’s capturing real life–not constructing an image. And most of what I do as a cinematographer–particularly in my work shooting spots and high-end corporate marketing projects–isn’t capturing random events and hoping they tell the right story, but crafting images that properly reflect a specific brand’s image and message.

The same is true of shooting drama. Framing a shot is only a small (albeit important) part of the whole. I think writing metaphors express this best:

- Lighting and lens choice are the paper upon which the story is told.

- Editing creates the rhythm of the sentences and paragraphs.

- Documentarians find the words and capture them so that they tell their own story.

- Cinematographers write specific words that can be edited together to tell the story that they’ve been hired to tell.

Constructing an image takes forethought. Constructing an image takes knowledge, taste, experience and talent. A lot of what I see on the air these days is basically documentary still photography in motion, and while the images can be stunning in their beauty a lot of it is… not.

Watching a camera operator direct an episode of a TV series reminded me of all the reasons I appreciate craftsmanship. It’s not just enough to capture the action and slam it together into something that shows off performances; the director and cinematographer must craft images that say specific things about the mood of the scene, the relationships of the characters, and how those relationships change over the course of the scene.

I’ll leave you with this clip. It’s the first five minutes of a TV series, and it’s possibly the best cold setup for a premise I’ve ever seen. I love the blocking of the actors in such a small space, the camera movement, and–particularly–the rhythm of the editing, which is made wholly possible by the specific shots chosen by the director and DP. There are modern TV shows that might try to capture this without a rehearsal, shooting on the fly with multiple cameras, capturing spontaneous performances and just “seeing what happens.” For me, though, that approach could never reproduce the power of a scene shot with the intent to tell a particular story, in a particular way, to evoke a specific set of emotions. Doc-style shooting has its place, but if you know what the story is that you’re trying to tell you’re immediately empowered to shape its telling. And that’s what a cinematographer does.